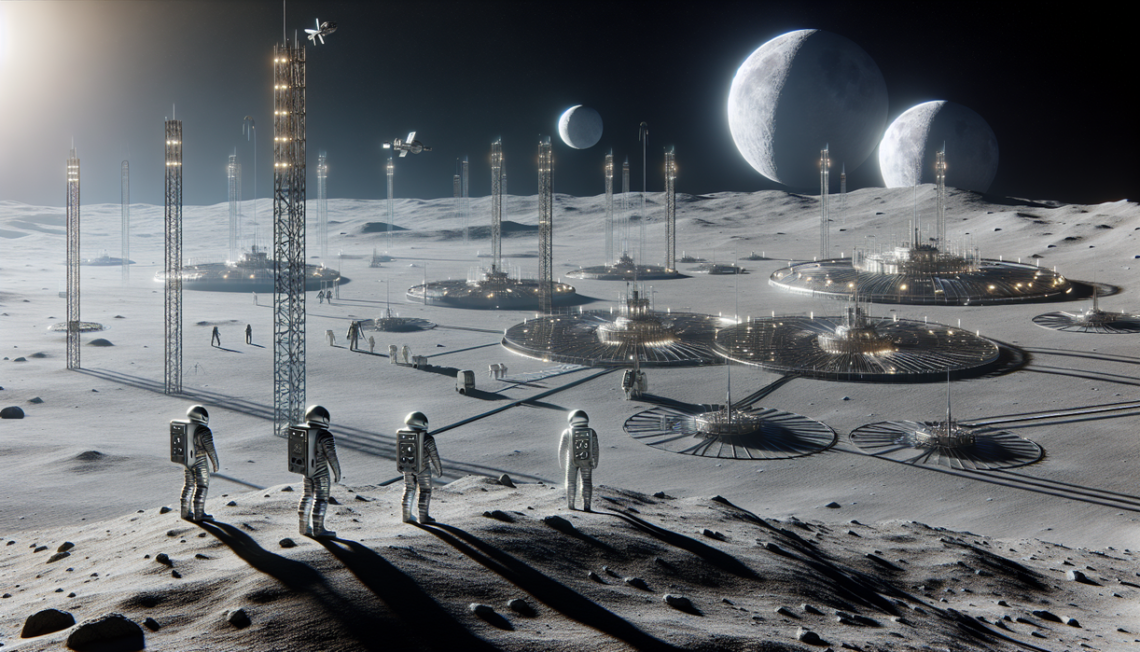

www.silkfaw.com – The rise of uncategorized lunar mega-projects is exposing a dangerous gap in our rules for outer space. Russia’s Selena initiative, reportedly a nuclear power station for the Moon by 2035, illustrates how national ambition races ahead while legal frameworks trail behind. The plan links to the Russo‑Chinese International Lunar Research Station, yet its core details remain opaque, loosely described, or simply uncategorized. That vagueness is not a minor paperwork issue. It reveals how our existing treaties struggle to cope with nuclear energy, military dual‑use technology, and AI‑driven autonomy operating off‑world.

When a project stays uncategorized, it slips through the cracks of oversight, public debate, and accountability. AI systems likely will manage power distribution, navigation, and safety protocols for any lunar nuclear plant, but their governance sits in a gray zone too. The Outer Space Treaty was drafted long before algorithmic decision‑making or permanent off‑Earth reactors seemed realistic. As Selena and similar programs move from concept art to construction timelines, humanity faces a stark question: can we afford to let the future of lunar infrastructure remain uncategorized in legal as well as ethical terms?

The uncategorized Moon: law lags behind ambition

Space law still leans on a handful of Cold War era treaties, all drafted when lunar bases felt like distant fiction. These texts treat the Moon as the “province of all humankind,” yet they stay uncategorized regarding many concrete technologies now under serious discussion. Nuclear reactors on the surface, autonomous excavation swarms, and AI‑directed research stations barely appear in their language. The legal system works reasonably well for satellites and crewed missions in low Earth orbit, but falls apart once we shift focus to permanent off‑world infrastructure.

The uncategorized status of projects such as Selena exposes three gaps. First, there is no shared standard for what counts as peaceful nuclear use on the Moon. Second, AI oversight in space activities remains undefined. Third, resource extraction rules hang in a limbo between non‑appropriation principles and emerging national legislation. These gaps invite strategic behavior. States can argue every novel system fits a peaceful, civilian label, even when it carries obvious military potential. That “dual‑use by design” model thrives whenever initiatives stay loosely defined or uncategorized on paper.

Selena sits at the crossroads of this legal fog. A lunar nuclear plant could supply robust power for deep‑space research, mining, and communications. It could also support surveillance networks, advanced weapons development, or denial strategies that restrict rivals’ access to valuable regions. Space law never anticipated comprehensive energy hubs on another world, so it remains uncategorized regarding rights, obligations, and liability. As a result, the first actors to build such systems might shape norms through practice rather than negotiation, forcing everyone else to adapt to precedents set by a few early movers.

AI, nuclear power, and the risks of an uncategorized frontier

AI plays a pivotal role in this unfolding story. Any lunar nuclear plant must operate with long communication delays, harsh environmental conditions, and minimal human presence on site. That reality almost guarantees a heavy reliance on autonomous or semi‑autonomous systems. Yet AI governance for space remains largely uncategorized, even on Earth we still struggle to regulate high‑risk applications. Algorithms deployed on the Moon could make life‑or‑death decisions for crews, robots, and surrounding infrastructure, far from direct human oversight.

Combine this with nuclear technology, and risk multiplies. Safety standards for terrestrial reactors evolved through painful accidents, regulatory reforms, and public scrutiny. A lunar facility would escape much of that pressure, especially if its design stays uncategorized behind national security arguments. If an incident throws radioactive material across a region of the Moon, who answers for the damage? Who measures it? Without transparent categories for such projects, the conversation often stops at “it is peaceful,” a claim impossible to verify without full disclosure. That secrecy fuels mistrust among rival states and private actors.

My personal concern lies less with any single country and more with the structural temptation to exploit ambiguity. When rules lack categories for AI‑managed reactors on extraterrestrial soil, decision‑makers enjoy wide discretion. They can underplay military connections, postpone safety investments, or sidestep global consultation. The result is a lunar frontier shaped by opaque choices rather than shared planning. An uncategorized approach enables short‑term strategic gains, but it deepens long‑term instability because others respond with suspicion, counter‑projects, and perhaps their own opaque deployments.

From uncategorized loopholes to a cooperative lunar charter

To avoid an era of uncategorized escalation on the Moon, we need a modern lunar charter forged through broad participation, including smaller nations and private entities, not just major powers. Such a framework should define clear categories for nuclear energy use, AI autonomy levels, environmental protection zones, and resource management practices. It must link transparency with access to joint projects, so cooperation offers more benefits than secrecy. My hope is that Selena, and similar initiatives, become catalysts for honest negotiation rather than symbols of a new arms‑length competition. The Moon’s future should not be shaped by whatever remains uncategorized; it should reflect deliberate choices about safety, fairness, and shared responsibility among all who look up at that distant light.